Yesterday, Tennessee Republicans expelled Reps Justin Jones and Justin Pearson, the only two young, Black lawmakers, from the state Legislature for supporting a youth-led protest that called for gun control after a deadly shooting in a Nashville elementary school. (How many of us reading this know exactly where we’re suppose to hide and check where the exit doors are when we enter classrooms? Yes, that’s how messed up school shootings are on us youth in schools.) Reps Jones and Pearson are part of the “Tennessee Three” (the third Rep. Gloria Johnson, a white female retired special education teacher was not expelled) that joined thousands of peaceful protesters, mostly students, calling for action against gun violence. Last week, my family and I did the same. We visited the Capitol with over 300 youths across the state (I missed school first time since we moved here), held our rally on the Capitol floor and met with policymakers on the human rights that have been taken away or under attack: reproductive rights, LGTBQIA+ healthcare and autonomy, voting rights, gun violence, criminal justice, and educational justice (including ethnic studies and Asian American Studies). What happened to Reps Jones and Pearson and what is happening in my state and our country is an attack on us – the youth, particularly those of us who are multiply marginalized. You all know how quiet I am in person, and I am reminding myself and y’all out there that we need to be loud now more than ever. We can not (and will not be) the model minority. We cannot be silent.

Model Minority Myth (The Need to Be Invisible)

Image from FARIHA RÓISÍN’s Jugganaut article titled “The Not-so Model Minority” that talks about the roots of the myth in American immigration and naturalization.

I struggle with how people see me (and how I see myself). The need to be silent, to be obedient, to have still bodies and minds – yes, the Model Minority Myth. The Model Minority seems positive, like a compliment (I spent most of my life trying to live up to it): We work hard. We don’t complain. We’re good at math (AND my mom is a math educator). You are always successful. The myth shows up with Asian Americans in media as all of crushing school and becoming super rich (we are not all “crazy rich Asians”) or the photos and videos of violence on our elderly and women (assuming we’re all meek and victims) attacked in the streets by men of color (even though data will show that the lead perpetrators are white men). I see this perpetuated in our community now as a high school student on acceleration (taking every AP class possible and joining every club to compete for college admissions) and assimilation (the fear to speak up and show up in marches, rallies, and school and city board meetings even on issues that impact us directly). We are not taught about the low rates of graduation for Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders or the disproportionate suicide rates among Asian American youths and young adults. The Model Minority Myth rewards this false narrative of “excellence” through individualism and competition. I hear it in my Asian American friends at school struggling with the internalized oppression to be something no one can be.

This myth has become a definition to create the one-size-fits all Asian, erasing the disparities between the 40+ ethnic groups that fall under the “Asian American” umbrella, further marginalizes those whose bodies and lives just won’t allow us to live up to it, and silences those who speak out against it. It’s also anti-Black at its core, and has long been weaponized against Black and Brown communities labeled “problem minorities” for fighting back against racism.

___________________________________________________________

Saving Face (Double Invisibility) 丢脸

Mo(ve)ments

Since our move to Texas, I notice more, maybe because everything is so different. I notice moments like what happened in the Tennessee Legislation with Reps Jones and Pearson (and their bravery despite losing something they had fought so hard for). Jones’ words about how moments of revelation and self and collective empowerment are not stoppable; these moments are central to starting movements. These moments can range from the Oscars to marginalized stories. I also think of Sandra Oh at the Golden Globes and Michelle Yeoh at the Grammys. These moments start and contribute to movements for change in film, in our local and state leadership, but also in reminding us all to be louder, to take up space, and to make our presence known. Other moments, such as stories of people I am about to share, start movements that intentionally center on resistance and strength.

___________________________________________________________

My Moment

“I think I spent most of my life trying to be the model minority but I couldn’t (and now wouldn’t).”

Origami has become my way of stimming (in ways that is kinda acceptable for others) in class, in cars, in restaurants, during debate rounds. If I don’t, one of the things I end up doing so that my body isn’t always swaying is that I pick my skin– even when it’s bleeding. My body has to move, like my mind. My body defies the model minority myth. My body refuses to be still, refuses to comply, refuses to be complacent.

___________________________________________________________

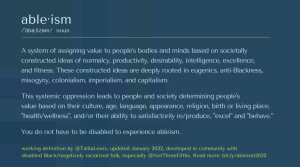

Ableism

I think my need to find socially acceptable ways of stemming relates to ableism. Ableism impacts all of us. In this zine, I intentionally focus on badass disabled AsAm female activists (those multiply marginalized) to challenge ableism and challenge the Model Minority Myth. Not all Asian Americans fit the one-size-fits-all mold of the myth; not all Asian Americans are meek and quiet. We are not a monolith.

___________________________________________________________

Moment: Alice Wong

Alice Wong, on her Disability Visibility website, self-describes as a disabled activist, writer, editor, media maker, and consultant. Alice’s voice is loud and impactful and she utilizes it to uplift others through spaces such as the Disability Visibility Project and book with the similar title, Disability Visibility. I met her three years ago when I was first learning about Asian American activists and changemakers. Alice herself is a moment. What I admire most about Alice is her dedication to amplifying disabled voices to create more moments. These stories – counterstories to the idea of disability as something other than beautiful – are a powerful form of resistance. These counterstories/ourstories center on moments that start mo(ve)ments. Alice exemplifies the need to take up space, bold leadership, and advocacy for what she and our communities need and deserve.

___________________________________________________________

Moment: Mia Mingus

Mia Mingus self-identifies as a queer, physically disabled, transnational adoptee and activist. The intersectionalities of her identities contribute to her work on collective access. Collective access has been a powerful new idea for me. Collective access is the idea that accessibility needs to be created with others. “Access is a constant process that doesn’t stop.” quote source Every person has access needs. This process needs to occur as a collective, with intentional commitment. I feel like structures (every kind of structure from stairway access to the way my high school runs) are often designed without attention to equity and accessibility and then access is thrown in as an afterthought. Mia, being a disabled feminist, queer, anti-racist, and an adoptee, the access needs of each identity are intertwined. There is no full access for Mia without LGBTQIA+ inclusion, healthcare for all, racial justice, as well as attention to protection for sexual assault as a survivor. Solidarity between all of these movements is vital. I am so inspired by Mia because her words (here I linked her amazing blog, Leaving Evidence) and actions are deeply rooted in togetherness. Togetherness challenges the model minority myth. We are not weak, meek, complacent, or perfect. It’s about the strength of who we are together.

_______________________________________________________

The Movement

I have been trying to identify how Mia and Alice are similar in their movement building. They are all part of so many things. We shouldn’t have to limit ourselves to one thing, one identity, one movement.

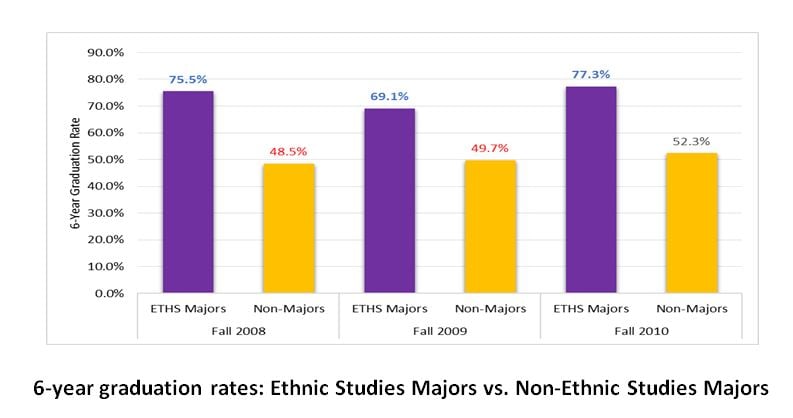

improvement in “male, female, Asian and Hispanic students… particularly concentrated among boys and Hispanic students.” The improvements made among these students were not only a result of the Ethnic Studies classes but specifically the curriculum of these classes. The curriculum of these courses aligns with a student’s individual experiences, aiding in increasing student’s engagement, and thus improving their grades and leading them to the path of academic success. Building from students’ lived experiences and daily lives kinda makes sense. School curriculum that connects to student’s life is just good curriculum.

improvement in “male, female, Asian and Hispanic students… particularly concentrated among boys and Hispanic students.” The improvements made among these students were not only a result of the Ethnic Studies classes but specifically the curriculum of these classes. The curriculum of these courses aligns with a student’s individual experiences, aiding in increasing student’s engagement, and thus improving their grades and leading them to the path of academic success. Building from students’ lived experiences and daily lives kinda makes sense. School curriculum that connects to student’s life is just good curriculum.  (

(

Historically, the Asian American community has the lowest voter turnout of any demographic! In the 2016 election, Asian American voting rates remain strikingly low, at 49%. When we don’t vote, we’re ignored! Republican and Democratic Parties continuously overlook Asian Americans. It’s sad to say but the dominant thought, “Why focus on AAPI needs if they don’t vote?” According to the 2016 National Asian American Survey, “70 percent of Asian American registered voters surveyed … have not been contacted by one of the political parties.” Right now, think about how often you have been contacted for this election? Should one’s social identity impact your value to politicians?

Historically, the Asian American community has the lowest voter turnout of any demographic! In the 2016 election, Asian American voting rates remain strikingly low, at 49%. When we don’t vote, we’re ignored! Republican and Democratic Parties continuously overlook Asian Americans. It’s sad to say but the dominant thought, “Why focus on AAPI needs if they don’t vote?” According to the 2016 National Asian American Survey, “70 percent of Asian American registered voters surveyed … have not been contacted by one of the political parties.” Right now, think about how often you have been contacted for this election? Should one’s social identity impact your value to politicians?